Sensing the importance of crayfish’s ability to smell

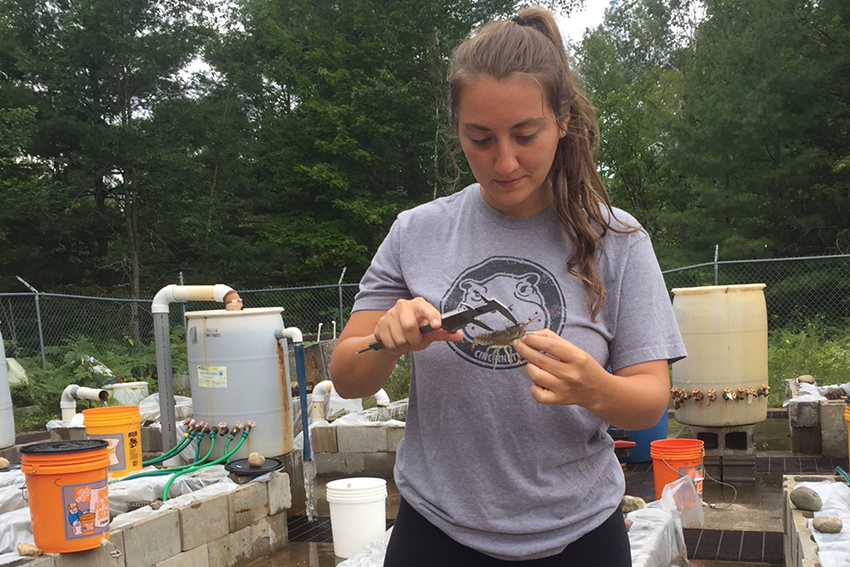

Field work puts BGSU graduate student Molly Beattie up close with crustaceans

By Matt Markey ’76

Koala bears are cuddly, elephants are so majestic, chimpanzees are playful,

meerkats so inquisitive, and rabbits are just plain fuzzy and cute. Crayfish, on the other hand, have those beady eyes, dangerous-looking claws, a hard shell and even a disturbing general name: crustacean.

Molly Beattie, a Bowling Green State University graduate student studying animal behavior, had always envisioned working with mammals, but she spent eight weeks this summer living at a remote research station in northern Michigan and handling crayfish every day. Beattie’s study required her to first catch crayfish, then transport them, house them, feed them, conduct daily trials involving the crayfish and chronicle their every move.

“I definitely was not comfortable handling them at first — I like mammals,” the Bowling Green native said. “Since I was handling them constantly, I became more comfortable with it as time went on, but I have to admit it was a bit weird for a while. It’s a lot different than working with mammals.”

“I definitely was not comfortable handling them at first — I like mammals,” the Bowling Green native said. “Since I was handling them constantly, I became more comfortable with it as time went on, but I have to admit it was a bit weird for a while. It’s a lot different than working with mammals.”

Beattie’s field research involved closely examining how the diet of a crayfish predator might impact the behavior of crayfish. She used a maze to analyze the behaviors exhibited by crayfish when certain dietary fish odors were present in the water.

“This study looked at crayfish, but ultimately, I’m interested in how animals make decisions,” said Beattie, who earned her undergraduate degree in biology with a chemistry minor.

Just as odors associated with the human body can change due to certain foods in the diet, such as garlic or asparagus, in Beattie’s study the predator fish were fed either a protein diet (worms), a vegetarian pellet diet or fed crayfish. Beattie placed the study’s crayfish in a controlled environment and recorded the behaviors exhibited by her test crayfish based on the different dietary fish odors present in the water.

“In particular, Molly is studying the role of dietary and species cues on the perception of predation risk in crayfish,” said Dr. Paul Moore, BGSU biological sciences professor who led a team of eight university graduate students that spent the summer conducting research at the facility. “Essentially, she feeds fish different diets and tries to determine whether the different diets impact the ability of other crayfish to determine the presence of a predator.”

The focus of her work was the native virile crayfish, but she also included the invasive rusty crayfish, which is considered a threat to Michigan's native crayfish population. Both species are freshwater crustaceans most often found in lakes and streams. Crayfish play an important role in the food web as one of the primary food sources for sport fish, birds and small mammals.

“I am interested in how fish diet affects crayfish behavior,” said Beattie, who conducted her summer study at the University of Michigan’s research post at Douglas Lake, in the northern reaches of the Lower Peninsula. The facility is surrounded by second-growth forest, with access to the 3,400-acre lake and the unique stream lab facility located on the Maple River.

After dark and using nets that she made, Beattie captured crayfish for the study on nearby Burt Lake. She conducted 137 trials over the course of the summer, using about 200 crayfish. The strict parameters of her work required that she house her fish for the study — the natural predator largemouth bass and non-native cichlids — in aerated tanks, and feed them a very specific diet for 48 hours prior to each testing session. The actual tests were conducted in an artificial stream she built with cinder blocks and plastic, with the water from the nearby river piped through it.

“We were up pretty early every day, we ate all of our meals together, and right after breakfast we were off to the stream lab to conduct the various experiments,” Beattie said. “I worked through lunch most of the days, and later in the afternoon it was time to clean up, transfer the videos to my computer, and then prepare for the next day’s experiments.”

Beattie kept a daily log of the size and sex of the crayfish she used in her project, and measured each fish before staging the tests. She conducted four trials a day on average, and recorded each crayfish for 15 minutes. She is analyzing those reactions and her data from the study back at BGSU this semester.

“I have about 120 videos to watch, and I will have to go through each one multiple times and compare them with my notes. It is definitely a lot of work,” said Beattie, who plans to present her thesis based on the research in the spring.

Moore said the other BGSU students at the research station conducted individual studies on topics such as social behavior in fish, ecotoxicology of different pollutants on crayfish and the effects of flow on the evolution of stonefly morphology. He said the predator-prey interactions such as the one Beattie examined are a critical component of aquatic food webs.

“These interactions determine which organisms are present within streams, rivers, and lakes, as well as how those ecosystems function,” he said. “Thus, understanding the sensory basis of these interactions allows us to maintain healthy fish and crayfish populations within streams, and monitor stream and river health.”

Moore said many aquatic organisms use their sense of smell to mate, eat, avoid predation and even locate shelters. He added that the presence of different chemicals (herbicides, pesticides and personal care products) in the waterway can disrupt the ability of aquatic organisms to use their sense of smell.

“Molly’s work helps to quantify how important a crayfish’s ability to smell is to its survival,” Moore said. “Molly is very insightful and an intuitive scientist. She understands how to construct experiments and how to monitor the success of these experiments she is running. She is quietly tireless in her work ethic and her care for detail when collecting data.”

Beattie said her research was rewarding on several levels, and she enjoyed the experience, despite the remote location and spartan conditions at the field station.

“I went into this blind, not knowing what to expect, and it was minimalist living for sure,” she said. “This definitely opened my eyes into all of the time and attention to detail that such a study requires. The best part is learning how to do actual science and to contribute to science. I hope that someday, people will be studying my work.”

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:27AM