Bacterial drones vs. tumors

BGSU biologist part of team developing tumor-killing method

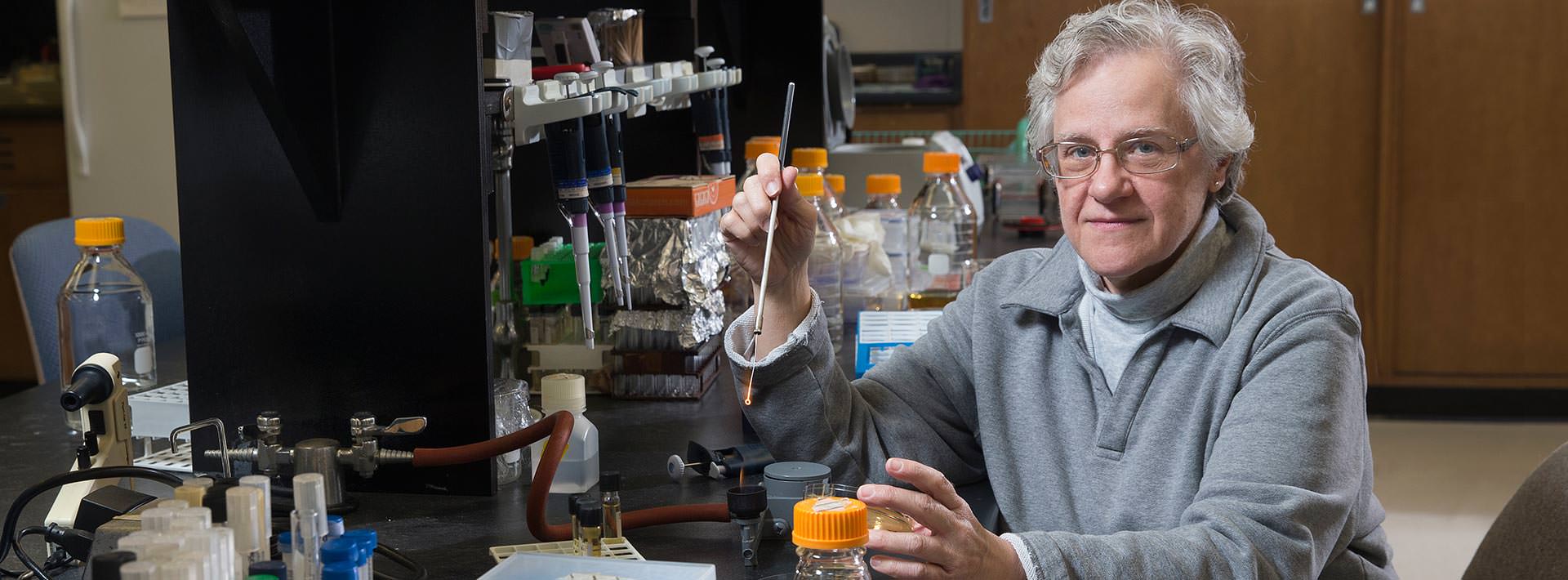

BGSU biologist Jill Zeilstra-Ryalls is working with University of Wyoming scientists to develop a method to counter a cancer tumor’s ability to fool immune cells and deliver programmable nonpathogenic bacteria directly to the tumor

BGSU biologist Jill Zeilstra-Ryalls is working with University of Wyoming scientists to develop a method to counter a cancer tumor’s ability to fool immune cells and deliver programmable nonpathogenic bacteria directly to the tumor

Talk of building smart bombs, counterintelligence and infrared light-guided delivery systems may have raised a curious eyebrow from anyone walking by the open conference room door on the sixth floor of the University of Wyoming (UW) building recently.

A peek at those gathered at the table may (or may not) have disarmed any alarm: molecular biologist Mark Gomelsky and immunologist Jason Gigley, both from UW, and BGSU biologist and bacteria-engineering expert Jill Zeilstra-Ryalls.

They were explaining their strategy: release special forces carrying programmed devices to infiltrate deep into an enemy’s territory, counter enemy propaganda, and then, using infrared light, trigger detonation without harming the surrounding population.

“Humankind is probably for the first time at the edge of actually curing most cancers ... I think this will happen in our lifetime. That is a bold statement. While most people don’t realize it, this is going to happen, and our own immune systems will be the key.”This interdisciplinary team – that also includes UW molecular biologist Anya Lyuksyutova – said the war on cancer will be won, and they want to use bacteria and the body’s own immune system to do it.

It’s not science fiction: it’s science.

“It sounds so far-fetched to think about bacteria in the bloodstream,” Zeilstra-Ryalls said. “Yet it’s working to purposefully inject the bacteria and not have it cause disease.”

“Humankind is probably for the first time at the edge of actually curing most cancers,” Gomelsky said. “I think this will happen in our lifetime. That is a bold statement. While most people don’t realize it, this is going to happen, and our own immune systems will be the key.”

They want to use what they call bacterial drones, or bactodrones, as cancer-targeting, remotely controlled weapons, in contrast to chemotherapy and radiation – the shotgun approach, Gomelsky said.

Key advances in immunology have opened new avenues of cancer treatment. Gomelsky said several companies are successfully using the weakened pathogenic bacteria listeria as an anticancer treatment in clinical trials.

They work with listeria as well, but the team wants to test the nonpathogenic bacteria Rhodobacter.

Bacteria tinkering specialist Zeilstra-Ryalls explained Rhodobacter bacteria can sneak under the radar of the immune system and reach tumors without causing disease anywhere in the body. Plus, these bacteria glow naturally in the presence of infrared light so they can reveal tumor locations in the body.

After spending time in Wyoming, Zeilstra-Ryalls continues her work back on BGSU’s campus. She and Gomelsky have previously collaborated on Rhodobacter projects.

Finding a way to induce a person’s immune system to fight tumors the same way the immune system fights infectious diseases was an exciting cancer-battling advance, Gomelsky said.

The survival of a tumor depends on its ability to trick immune cells to stand down.

“Tumors turn the immune cells into their companions and servants, so to speak,” Gomelsky said.

Advances in the study of tumor microenvironments have revealed how tumors trick immune cells. Turns out that, because of this trickery, bacteria can accumulate and survive inside tumors. The body’s immune system attacks bacteria in healthy tissues, but does little to bacteria growing inside tumors.

The team wants to use that free pass to “intoxicate” tumors and overcome the tumor’s no-worries directive to immune cells.

The scientists already know how to engineer genes into bacteria that encode products toxic to tumor cells and those that can awaken the immune cells from the tumor-imposed stupor.

“We want to help the immune system recognize tumors just like it recognizes pathogens. Once the immune system is mobilized, it can start fighting tumors,” Gomelsky said.

Enormous progress has been made recently in removing those tumor immunity directives using specific antibodies, but in many cases the awakened immune cells still don’t recognize the cancer cells as invaders. Immune cells may be ready to fight but need to know what to attack, Gomelsky said.

The team believes that, by exposing tumor cells killed by bacteria, they will alert immune cells to what they should attack.

“Bacteria serve as a vehicle for delivering genes we want inside the tumor,” Gomelsky said. “We also want to control when these genes begin to work inside tumors.”

Not easy to do, he said.

“You can trigger the production of these tumor-killing and immune cell-awakening bacteria with something as benign as light,” Gomelsky said. “The same kind of near-infrared light that is used in remote control devices for televisions and other electronics.”

Infrared light penetrates deep into human tissues.

“The genetic tools that we are developing will allow us to remotely control the bacteria inside tumors,” he said.

Critical discoveries in immunology have unlocked secrets of the tumor microenvironment, noted Gigley.

“Tumors are your own self, and a natural part of the immune system is to not fight yourself,” he said. “Tumors have been very difficult to target because of that.”

The point of using a bacteria-based system is not only to kill the tumor that’s present at the time, but to retain immunological memory – the immune system will remember and kill tumor cells and not allow the cancer to recur, he noted.

There are obstacles to the team’s success – lack of adequate funding and physicians’ skepticism about injecting cancer patients with live bacteria.

“We have yet to show that we can control bacteria inside the body,” Gomelsky said. “We have developed this technology and are on the verge of demonstrating it. Not yet in humans … but in mice as a starting point.”

The scientists are working to obtain additional funding as a means of continuing the research. "The public could help by telling their representatives how important funding is to the future of science in the country," Zeilstra-Ryalls explained.

“It’s so important that the public be aware of the need for research; no one can predict the next cure for cancer," she stated.

Julie Carle, BGSU, contributed to this story, written by Steven L. Miller, University of Wisconsin Extension

Updated: 01/25/2018 08:19AM