Birth of a Novel

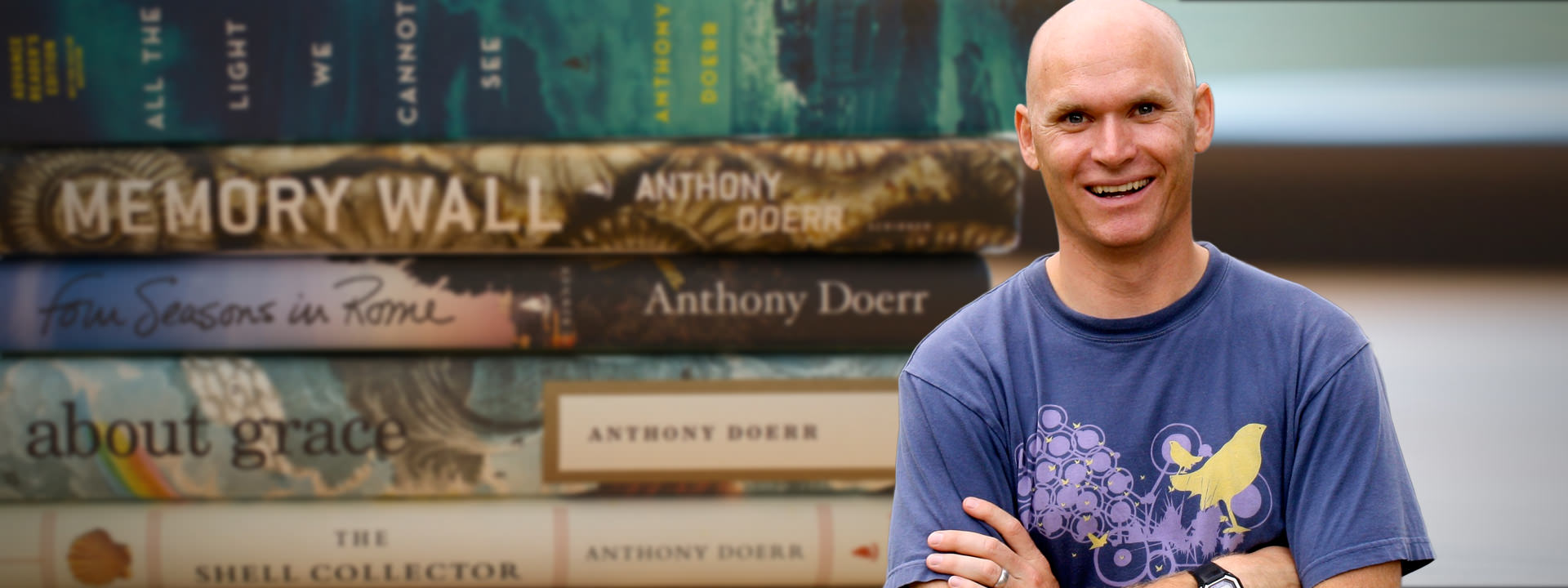

Anthony Doerr captures war and wonder

By Ann Krebs

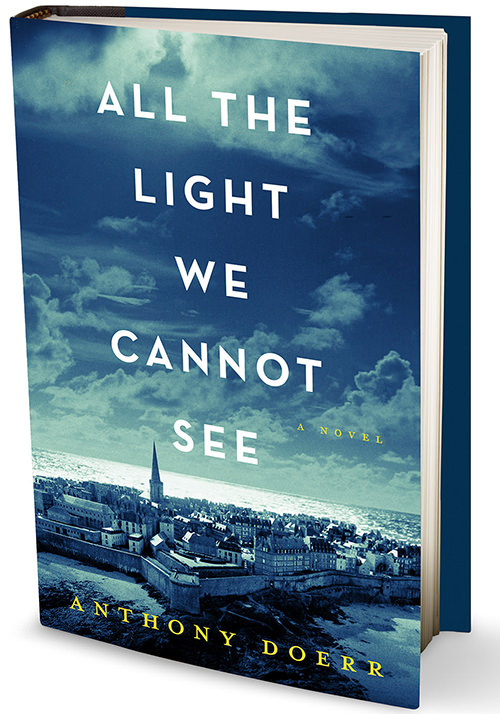

Award-winning short story writer Anthony Doerr '99 has earned another accolade for his best-selling novel "All the Light We Cannot See." The World War II novel that tells the parallel stories of a blind French girl and a young German soldier won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

The novel, more than 10 years in the making, is about World War II, blindness, children, a mythical diamond, the power of radio and the ways people try to be good to one another.

“All the Light We Cannot See,” published by Scribner, hit the New York Times best seller list at No. 10. Doerr, an alumnus of the Creative Writing Program, has been on a cross-country book tour since May 6.

As described on Doerr’s website, Marie-Laure lives with her father in Paris within walking distance of the Museum of Natural History, where he works. When she is 6, Marie-Laure goes blind, and her father builds her a model of their neighborhood so she can navigate the streets. When the Germans occupy Paris, father and daughter flee to Saint-Malo on the Brittany coast, where Marie-Laure’s agoraphobic great uncle lives in a house by the sea wall.

In another world, in Germany, an orphan boy, Werner, grows up with his younger sister, Jutta, both enchanted by a crude radio Werner finds. He becomes a master at building and fixing radios, a talent that wins him a place at an elite but brutal military academy and, ultimately, makes him a highly specialized tracker of the Resistance. Werner travels through the heart of Hitler Youth to the far-flung outskirts of Russia, and finally into Saint-Malo, where his path converges with Marie-Laure.

Doerr explained that the story is about radio and the way it was used as a tool both of control and resistance in World War II. “But it’s also about the lives of children, about color and light, and about wonder,” Doerr said. “If I had to choose a central theme, I’d probably say it’s the same question Werner’s sister asks him early in the novel: ‘Is it right to do something just because everyone else is doing it?’ Werner would prefer not to question himself or others about the repercussions of his actions, or even the repercussions of the actions of the Third Reich, but ultimately that becomes impossible for him.”

The book took a decade to write because of its intricacies and the fact that it required loads of research. In most of Doerr’s fiction to this point, he was working with contemporary settings. “But now I was working in the late 1930s and early 1940s,” he said, “and didn’t immediately know, for example, what sort of meals German orphans would be eating in 1937, or what a blind French girl’s schooling situation might be like, or if there were refrigerators in Parisian kitchens in 1940, or electric lamps on the streets of a mining town in Germany, etc. Anytime I had young Marie-Laure go to her dresser I had to stop writing for an hour, and start paging through old photographs.”

The book took a decade to write because of its intricacies and the fact that it required loads of research. In most of Doerr’s fiction to this point, he was working with contemporary settings. “But now I was working in the late 1930s and early 1940s,” he said, “and didn’t immediately know, for example, what sort of meals German orphans would be eating in 1937, or what a blind French girl’s schooling situation might be like, or if there were refrigerators in Parisian kitchens in 1940, or electric lamps on the streets of a mining town in Germany, etc. Anytime I had young Marie-Laure go to her dresser I had to stop writing for an hour, and start paging through old photographs.”

Another reason the book took so long was that the subject matter was difficult. “The Nazi regime committed atrocities on so many different levels, and reading about them in such detail tended to make me feel lousy. So I wrote two whole books (“Memory Wall” and “Four Seasons in Rome”) just as procrastination from writing this novel, really as a way to take a breath and step away from the material.”

Doerr did plenty of research online, but nothing could stand in for actually visiting places, so he ended up taking three separate trips to Europe during the creation of the book.

He said he has a soft spot for his character Frederick, who is a friend of Werner’s at the elite Nazi school they attend for much of the novel. “Frederick is, in many ways, a fictionalized version of one of my sons,” Doerr said. “He’s a very sensitive person who pays attention to things others don’t (birds, particularly). In the brutally competitive and conformist environment of the school, it’s a fatal weakness. There’s a line in the novel: ‘What the war did to dreamers.’ That’s what I’d think about when I was writing Frederick’s scenes. I’d look at my son and think: but for the grace of God, that could be you.”

Doerr lives in Boise, Idaho, with his wife and two sons. He received a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from BGSU and in 2010 was named one of the University’s 100 Most Prominent Alumni. He has won four O. Henry Prizes, three Pushcart Prizes, the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize, the Rome Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, the National Magazine Award for Fiction, the Pacific Northwest Book Award, three Ohioana Book Awards, the 2010 Story Prize, which is considered the most prestigious prize in the U.S. for a collection of short stories, and the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award, which is the largest prize in the world for a single short story. His books have twice been named a New York Times Notable Book and an American Library Association Book of the Year, and made lots of other year-end “Best Of” lists.

He still keeps in touch with those in the BGSU community, especially Dr. Wendell Mayo, a creative writing faculty member in the Department of English, and fellow author and alumnus Alan Heathcock ’96.

“Al lives in Boise, too, so I see him regularly and am a big fan of his writing (check out his searing book ‘Volt’ if you haven’t),” Doerr said. “I just had the privilege of reading an advance copy of Dr. Sharona Muir’s (also in the Department of English) forthcoming book, ‘Invisible Beasts.’ It’s an incredibly inventive and beautiful and strange book and it comes out in July. And I loved Dr. Mayo’s new collection, ‘The Cucumber King of Kedainiai’; he’s built a funny, haunting, sad, and exquisite series of windows into life in Lithuania. Wendell will always be one of my literary heroes.”

What advice does Doerr have for students who aspire to write? “Read, read, read, read, read.”

Some of the authors he loves include Anne Carson, Cormac McCarthy, Virginia Woolf, Jim Shepard, Denis Johnson, Bruce Chatwin, Ryszard Kapuściński, Tolstoy, Hilary Mantel . . . and hundreds more. Doerr said he’s learned something from each of them.

Students might also be interested to know that Doerr’s schedule is pretty regimented, like the schedules of most novelists. He works every weekday, and is usually at work well before 9 a.m. But there are lots of elements to being an author besides writing, like booking flights, reading proofs, teaching, touring, working with translators, and answering questions for interviews.

Asked if he sees himself as an “American” author and Idaho as an influence, Doerr responded, “Sure, of course I’m American, but perhaps I’m a little unusual in that, unlike so many American novelists, I don’t focus directly on American tropes or characters or cultural moments. I am much more interested in the planet’s history and topography and climate than I am in its geopolitics, and in the new novel the United States is really only present as an onrushing force of bombers following the invasion of Normandy.

“As for Idaho, yes, the place influences me every day, which in turn probably influences my writing. Idaho’s mountains and foothills and rivers are where I go to find sanity, whether it’s by fishing or skiing or biking or gardening or walking, so Idaho is a huge part of my life.”

Doerr will be busy with the book tour through September. For his next project, he’s been commissioned by a museum in North Carolina to write a piece about the Panama Canal to go alongside an exhibit commemorating the 100th anniversary of the canal’s completion. “So I’m up to my neck in dredges and Teddy Roosevelt and yellow fever at the moment,” he said.

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:51AM