A look at 100 years of voting rights

Constitution of United States of America

Amendment XIX

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Liggett and Jackson reflect on how far we've come and where there is still work to do

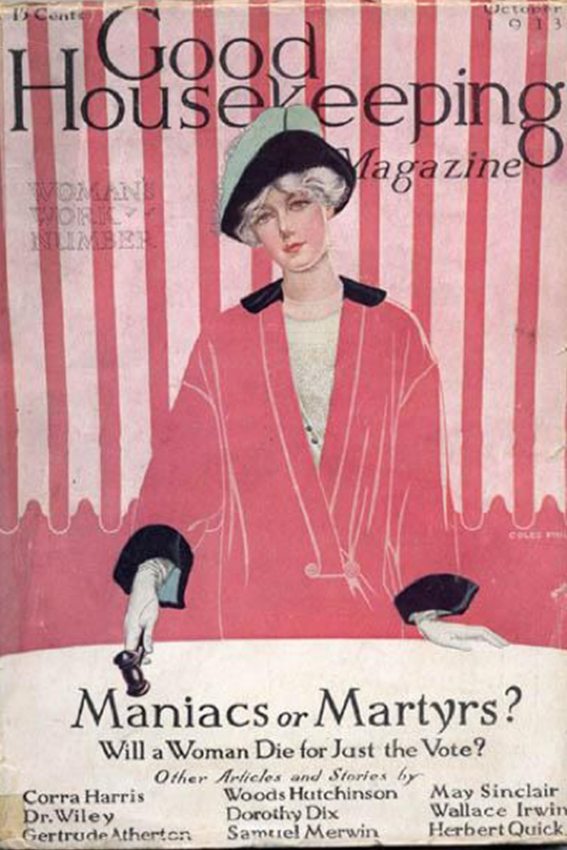

As the nation recognizes the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment that extended voting rights to American women, there is cause for celebration and for reflection.

Dr. Nicole Jackson, associate professor of history at Bowling Green State University, said, “Sometimes in these moments, it’s nice to reflect about how far we have come and, in some cases, how far we have not come.”

“The amendment did allow for women to become full citizens with enfranchisement,” said Dr. Lori Liggett, a professor of communication in the School of Media and Communication. However, for decades, loopholes were used to prevent many women of color from exercising their Constitutional right to vote.

“Historically, women, people of color and poor white men were not enfranchised citizens of the United States, and it took 144 years from the signing of the Declaration of Independence for some segments of women to become legal voters,” Liggett said. This made it “the longest, continuous reform movement in the history of our country.

“The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is typically considered the starting point of the movement. In truth, the efforts to secure legal, economic and political rights for American women began when the country was founded.”

The 19th Amendment, along with the 15th Amendment (which gave Black men the right to vote in 1870), “went a long way in changing the weight that Americans put on the access to voting,” Jackson said. “You also see the possibilities that emerged of people using their vote to change the government significantly.”

Jackson said it is important to remember that because suffrage is so bound up in abolition, the common thought is that they are fighting for the right for what all freeborn white men have. The reality was that voting rights were given to property owners. “We forget that when talking about voting rights, we are also talking about people who were working class or poor, rural people who were not property owners, as well as people who do not consider it significant for them to vote,” Jackson said.

Before the mid-19th century, voting was not considered a universal right of American citizenship. It took so long to achieve because they had to change the way every American thought about suffrage. “So not just white men who were able to vote, but also Black people and white women and even the everyday citizen had to think differently about their own access to voting,” she said.

She explained that right after the Civil War, Black men tried to change the government to build the possibility for public education, to use governmental employment to pull people out of poverty and to change the significance of various constituencies. Their efforts were stopped because of Jim Crow laws.

Once the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, similar efforts emerged. “Reformers began to lobby politicians based on the idea of winning the women’s vote now that it was a viable constituency,” Jackson said. “That was really an immediate change that continues to be a part of American political life.”

Change was not universal

“Sometimes popular media talk about how much progress we’ve made, but I think it’s important to take a step back and think critically about the moment, especially because the Voting Rights Act was gutted a few years ago and we are in a moment when voting access has become harder,” Jackson said.

What didn’t change is the “fairy tale that if you just give women, in particular white women, the right to vote you will start to see politics become clean,” she said.

“They will take this moral imperative that society says women have and they will make politics a place that is safe for women, but that doesn’t happen,” she said.

“That’s something to talk about, because they are not any better or worse than male voters. They are just people.”

When suffragists were advocating for adding women to the voter rolls, they promoted the idea that doing so would increase the number of Americans engaging enthusiastically with the political system. “Adding women to the voter rolls didn’t drastically change the percentage of Americans who do vote,” Jackson said. “And that remains pretty true to this day.”

Suffragists message was also that if women were given the right to vote, their positions would start to change socially and economically. “Unfortunately, that’s also not true.”

Presidential candidate Joe Biden’s vice-presidential pick of Sen. Kamala Harris, D-California, is a significant step in American politics and a nod to progress.

However, “politics is an ‘old boys club’ even when there are women in it now,” Jackson said.

“The amendment didn’t change the systemic racism against women of color or misogynistic attitudes toward all women,” Liggett added.

“You see various women’s issues either struggling to become national issues or becoming national issues only when they are controversial, like abortion,” she said. “But for the longest time, welfare was controversial and was only sold when it was aimed at women, even though women have no say in the kinds of welfare they would like to have access to.”

In the 1960s, there was a push to fund domestic violence shelters, which was considered primarily a women’s issue. When that became controversial, it was not considered a national issue, which points to how inconsistent politics handles such topics.

Coverture shaped American colonies’ laws

For current generations, it’s easy to forget that what they know now is not always the way it was. Prior to the 19th amendment passage, women had no representation in the laws that governed their lives.

“They could have opinions, but opinions do not protect rights,” Liggett said. The American colonies based their laws on English Common Law, which said “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in the law.” The woman’s legal rights and obligations were suspended during marriage.

“If a woman earned wages, that money belong to her husband or father. Women could not inherit land or property or sign contracts. Everything a woman had, even her clothing, belonged to her husband,” Liggett said.

“Women could not sue for injuries and they could not serve on juries. They were not entitled to education. They could be punished and even beaten by their fathers or husbands with very little legal protection.

“And of course, women could not vote, so that meant they had no influence on lawmakers,” she said.

Prior to the ratification of the 19th Amendment, women's roles in society had already begun to change by the 1890s. Young women sought higher education and went to college; women became wage earners and learned trades and professional skills; women took to the outdoors and engaged in athletics; and women became interested in learning about their own reproductive rights and health care needs.

“So, times, they were a-changin'!” Liggett said, “But women in elected political and governmental roles, especially at the national level, was almost unheard of."

Trailblazing suffragists/politicians

The movement as we remember it today, was a national movement whose leaders became nationally known, famous and infamous.

There were many trailblazers to the movement. From the known names of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth to the lesser-known names of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Anna Julia Cooper, many voices helped carry the message and push the movement to eventual passage.

Jeannette Rankin of Montana, in 1916 was the first woman to hold federal office in the U.S. when she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. “While we might marvel that she accomplished this four years before the passage of the 19th Amendment, we should remember that it was also 140 years after the U.S. became an independent nation,” Liggett said.

Fifty years after the amendment passed, Congress had only one female senator and 10 female representatives. Today, another 50 years later, there are 127 women voting in Congress. That is the most there has ever been, but still represents about one-quarter of the legislature

Locally, Bowling Green State University benefited from Wood County’s first female state representative Myrna Reese Hanna, whose legislative efforts in 1929 changed Bowling Green Normal School to Bowling Green State College.

In addition to the recognizable names of people who did much of the work for decades are the thousands of people in small towns and rural areas across the country who disrupted social norms for something probably most of them thought could never happen.

“We forget about the Black “club women,” many of whom were denied entry to most of the elitist suffragist organizations who feared ‘integrating’ membership would cost them support of Southern states,” Liggett said.

Many Black women were interested in having the right to vote because they knew without it they could not push back the ways in which their civil rights were being infringed upon as citizens, Jackson explained. “However, I would argue that Black women were not universally behind the vote either.”

If Black men had not been barred from voting because of Jim Crow laws, there were many Black women who were perfectly fine with the head of household voting for them, she said.

“The best minds of Black suffragists really understood what was true with the 15th Amendment and decades later with the Civil Rights and Voting Rights act, was there is no possibility for an equal citizenship that bars people from the right to vote. Whether that is about gender or race, they understood the need for universal suffrage,” Jackson said.

The stories of those women and the men who marched for female enfranchisement are emerging now, providing what will become a more complex version of the women’s suffrage movement.

Not perfect, but it changed America forever

In retrospect, the movement was multi-generational and involved women and men from all walks of life. And sadly, none of its first pioneer activists lived to see the passage of the 19th Amendment.

“Each new generation had to carry on the work of their predecessors -- and if they hadn't, you and I probably would not be able to vote even today,” Liggett said.

“Social and political movements need to motivate people to collectively transform laws, policies, and regulations whether at the local, state or national level," she said. “I try to teach my students that activism is only performance if the outcome is not legal protection."

“The real power of operating from an intersectional perspective comes from people collaborating to change laws, and we only change laws when we change the people who are making these laws,” Liggett said. “That is the legacy of the women’s suffrage movement. It’s not a perfect movement, but it changed America forever.”

Note: Jackson and Liggett were Fellows for the BGSU Institute for the Study of Culture and Society (ICS) for 2019-20. Liggett’s research project, “The Bicycle and the Ballot Box: How American Suffragists Pedaled Their Way to Power,” marked the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. Jackson’s project, “Women Writing Black to the British Empire,” developed from her new work on the British Caribbean Arts Movement of the late 1960s-1970s.

Updated: 08/31/2020 08:57AM