BGSU researchers trying to solve Lake Erie’s harmful algal blooms with new approach

Using hydrogels to reclaim nutrients from manure could help reduce agricultural runoff

By Bob Cunningham ’18

The Lake Erie region may soon have its watershed moment when it comes to curbing agricultural runoff thanks to researchers at Bowling Green State University.

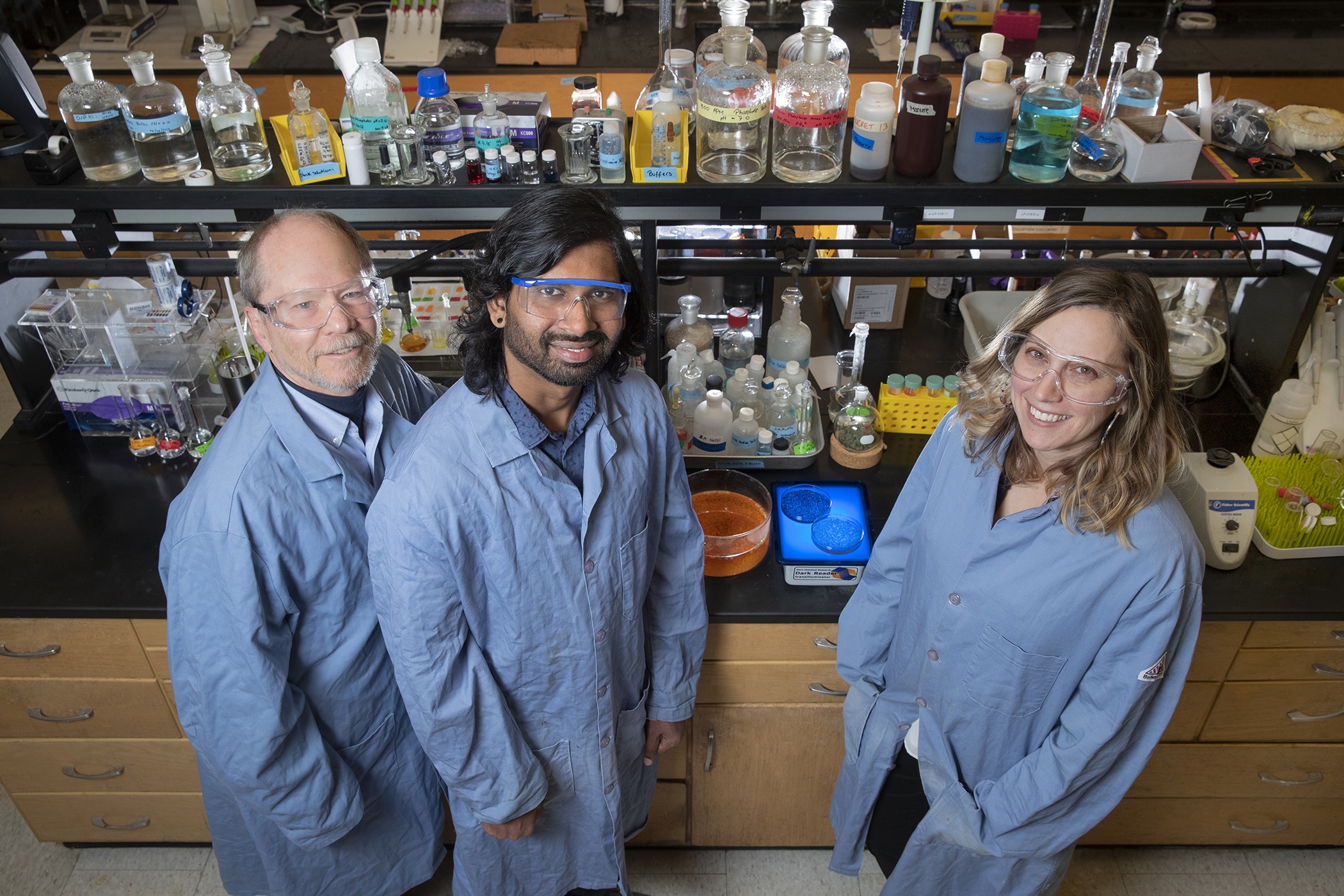

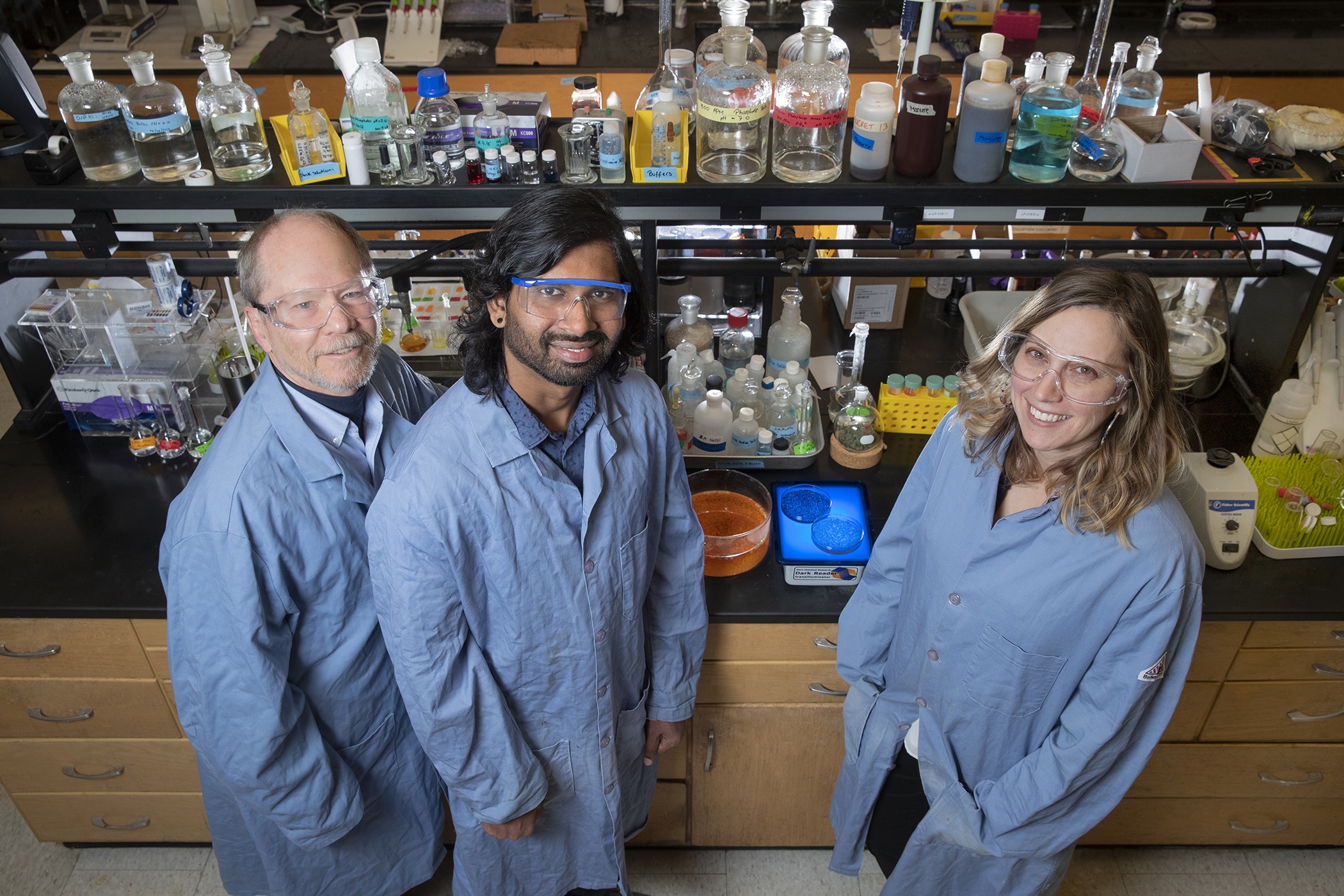

Drs. Alexis Ostrowski and Robert Midden and doctoral candidate Jayan Karunarathna recently had their research paper, "Reclaiming Phosphate from Waste Solutions with Fe(III)–Polysaccharide Hydrogel Beads for Photo-Controlled-Release Fertilizer,” published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. The research article was featured on the front cover of the journal, a recognition of the outstanding work that only 11 of over 90 manuscripts published in the journal receive each year.

Ostrowski received a five-year grant from the American Chemical Society’s Herman Frasch Foundation for Agricultural Chemistry to support graduate and undergraduate research to use the Fe(III)-polysaccharide hydrogels to reclaim nutrients from manure and help reduce agricultural runoff. The research studies how to turn liquid waste from concentrated animal feeding operations into fertilizers by encapsulating the nutrients into a solid form so that they may be safely transported and spread on fields.

Runoff pollution, which occurs when rainfall washes fertilizer and manure that covers large farm fields in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan are a major contributor for Lake Erie's harmful algal blooms (HABs). The runoff flows into streams and eventually into the lake. The goal of this project is to separate the nutrients such as ammonium and phosphates from the wastewater which promote the growth of algae. This way the collected nutrients can be recycled as fertilizer.

“When it rains, the farms’ holding ponds of heavy nutrients overflow and that’s what eventually causes harmful algal blooms,” said Ostrowski, an associate professor in the Chemistry Department of the College of Arts and Sciences. "Farmers ‘de-water’ the waste solution in order to separate the water and the animal waste so they can use the water for irrigation and the waste for the fertilizer. It’s problematic because fertilizer ends up being water-based and ends up in Lake Erie.”

The researchers use natural polysaccharides extracted from sea weed, fruit peels, shells of crabs and shrimp to make soft hydrogels which can absorb the rich nutrients from wastewater. This innovation possibly could save farmers a lot of money and is relatively easy to do, said Midden, the former associate vice provost for experimental and innovative learning.

The article, published in November, details how “photo-responsive hydrogels from sustainable sources, ferric ions (Fe3+) and polysaccharides, can reclaim and recycle phosphate from waste solutions, including animal waste. After exposure to sunlight, the hydrogels degrade to release the phosphate as fertilizer for plants.”

In other words, the slow release of nutrients from these degradable gels with the help of sunlight make them efficient and environment friendly — especially for Lake Erie.

Karunarathna’s plant trials in Bowling Green’s campus greenhouse showed complete degradation of the hydrogels in less than two weeks. Also, enhanced plant growth with nutrient-loaded beads compared to controls indicated nutrient release with no signs of iron toxicity, according to the paper. These results show that the hydrogels were able to “reclaim phosphates from waste solutions and can be used as a controlled-release fertilizer.”

Karunarathna is the only graduate student to work on this project along with several undergraduate students in testing and developing the hydrogel fertilizer system. The team is currently working on patenting their novel light-controlled fertilizer release system.

“It is amazing how this project evolved from a concept to a successful wastewater treatment and nutrient release system,” Karunarathna said. “As scientists, if we are not trying to solve these issues, nobody will.”

The researchers are currently working on another research paper with their most recent findings with tomato plant trials.

This research, which aligns with the University’s mission of contributing to the public good, has the potential to help solve Lake Erie’s harmful algal bloom problem by severely reducing the amounts of heavy nutrients being introduced to the soil and streams in the region.

“As a public university for the public good, our faculty have the potential to make an impact in on our community through research, collaboration and discovery,” BGSU President Rodney K. Rogers said. “Through our faculty’s excellence in teaching, research and outreach, BGSU builds a collaborative, diverse and inclusive community where creative ideas, new knowledge, and entrepreneurial achievements can benefit others in our region, the state of Ohio, the nation and the world.”

BGSU’s initiative to contribute to the public good can inspire research, Ostrowski said.

“The thing that’s important to me, and I know it’s important to Jayan as well, is we have to think about our work: How can this research be used for public good?” she said. “What are problems that we see in our local community that with our knowledge we could help solve that problem? We had these materials that decompose when you shine light on them, so you start to thinking, what could use them in actual, real-world applications?

“It’s really changing the traditional thinking in science, which is taking the fundamental understanding of principles and theories of how things work and, now, trying to take that a step further. Once we know that, we can apply those theories to solve a problem in our community.”

Midden also looks forward to the impact of their research on public good.

“Our teams’ research is able to contribute to the public good; by using these methods we can reduce the amount of excess materials, hopefully eliminate harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie and also introduce best practices for farmers to save money,” Midden said. “Once it gets going, not only will it help farmers in northwest Ohio, but also farmers in Indiana and Michigan won’t want to miss out on the cost savings.”

The research led to collaboration in other fields of research and with other departments. Ostrowski has started a collaboration with the BGSU Department of Biological Sciences to assess the effect of these gel beads towards soil microbial communities.

“Jayan is a chemist but he started his project in the greenhouse, which is more environmental science or biology,” Ostrowski said. “But when you’re answering the question — how can this solve a particular problem? — you go where the science leads you.”

Updated: 06/10/2021 01:08PM