Mother’s Experiences of Unintended Childbearing, 2017

Family Profile No. 3, 2021

Author: Karen Benjamin Guzzo

The majority of births in recent years are intended (FP-21-01), but many mothers nonetheless experience unintended fertility. In this profile, we examine the share of mothers aged 45-49 who have ever experienced unintended childbearing (having any births that are not ‘on time’) for the year 2017, using the 2015-2019 cycle of the National Survey of Family Growth. Unintended births were identified from a series of questions in which women were asked to characterize each birth as on time, mistimed (wanted but occurring earlier than desired), or unwanted (the respondent did not want any births at all, or no additional births). When births were reported as too early, women were asked how much earlier than desired the birth occurred, and we categorize mistimed births into two groups: slightly mistimed (less than two years earlier than desired) or seriously mistimed (two or more years too early). This profile is an update of FP-17-10(1) and the third in a series on unintended childbearing.

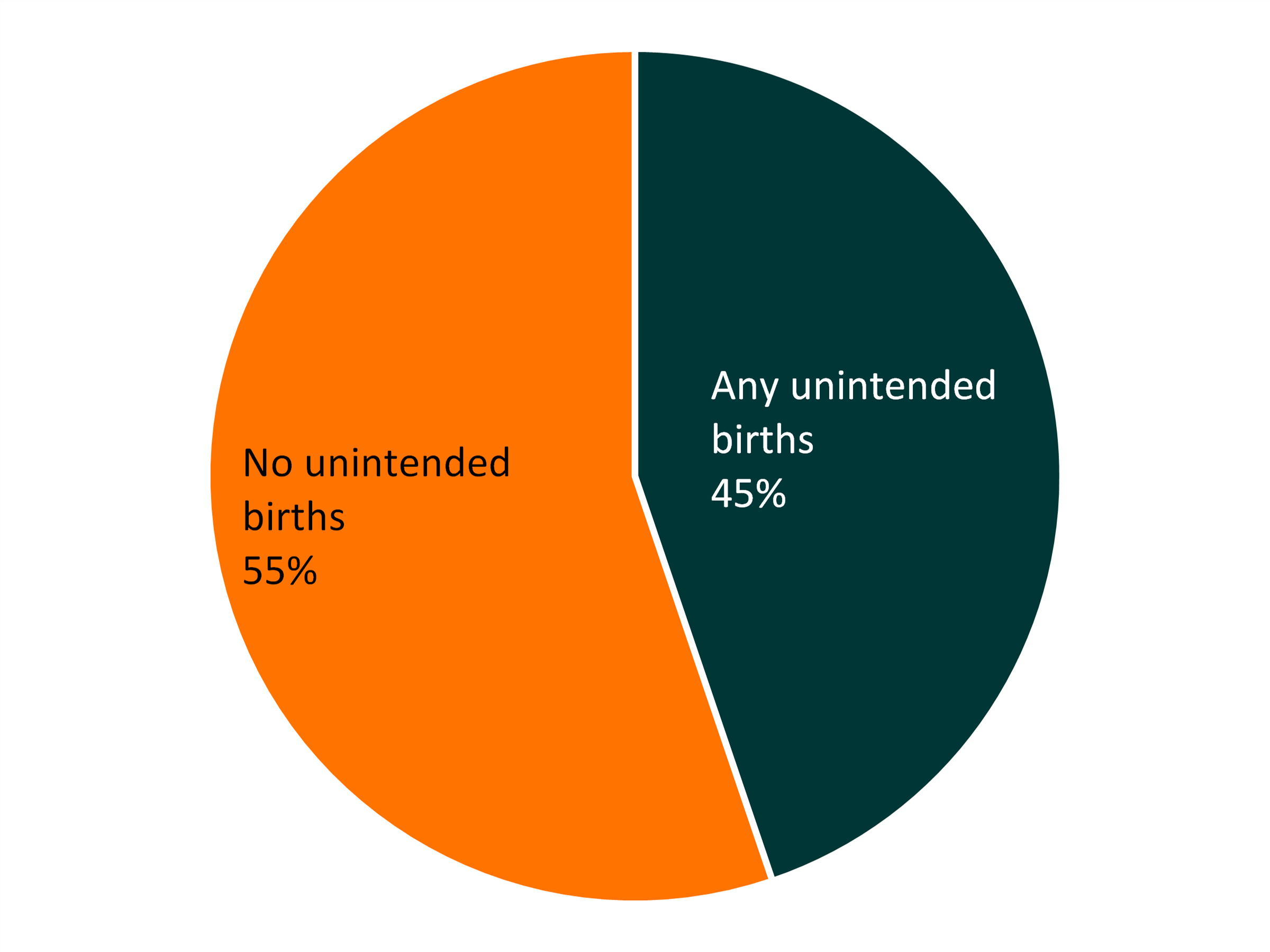

- In 2017, 45% of all mothers aged 45-49 had experienced at least unintended birth (figure 1).

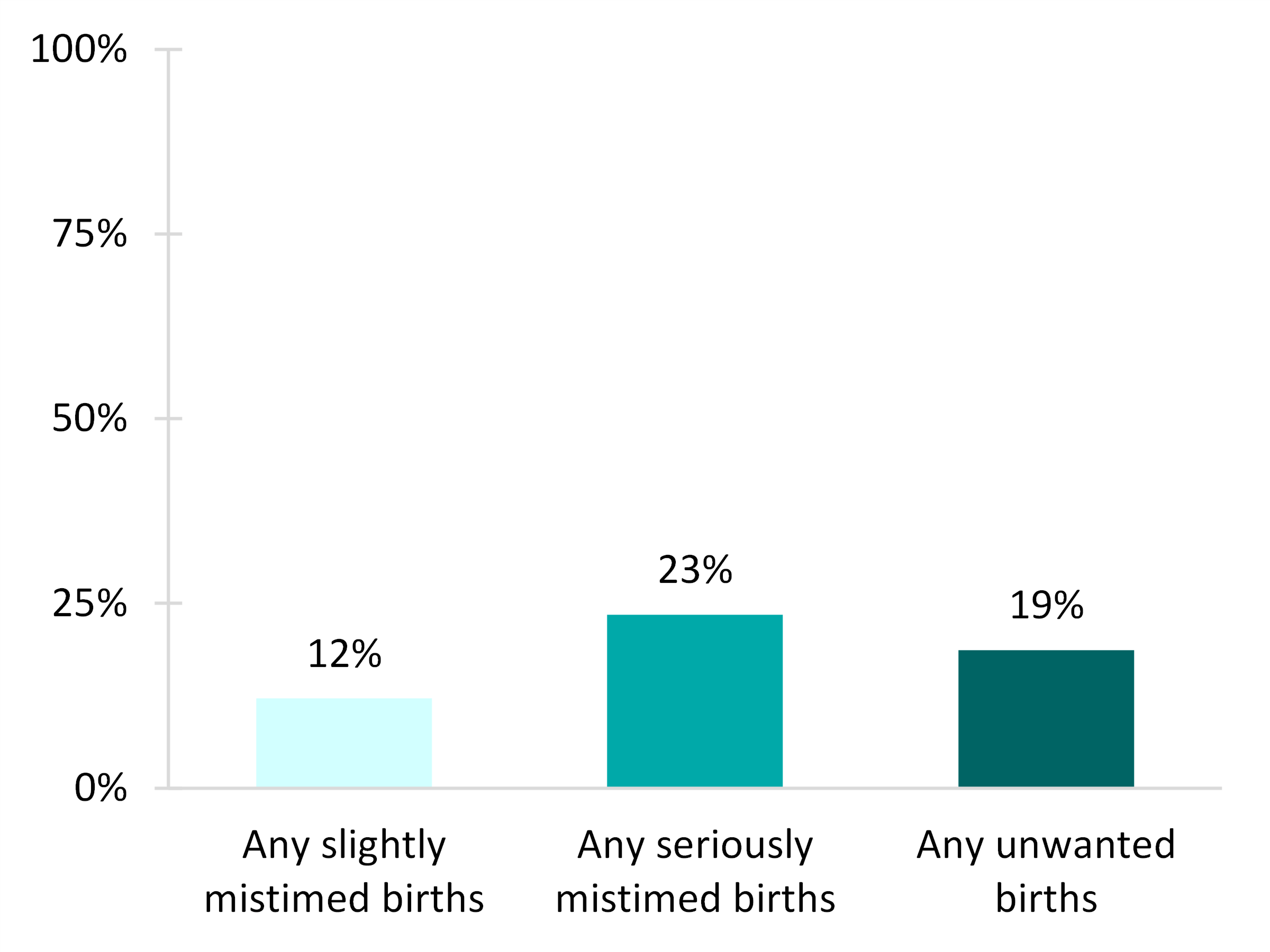

- Seriously mistimed births were the most common type of unintended birth, with nearly one-quarter of mothers (23%) having had at least one such birth (figure 2).

- About one-fifth of mothers (19%) have had an unwanted birth (figure 2).

Figure 1. Unintended Births Among Mothers Aged 45-49, 2017

Figure 2. Experiences of Unintended Births Among Mothers Aged 45-49, 2017

Age and Unintended Childbearing

- Among mothers 45-49 in 2017, those with only intended births had a median age at first birth of 28 years.

- Mothers with any unintended births began childbearing much earlier, with a median age of 20 years.

In 2017, 45% of all mothers aged 45-49 had experienced at least unintended birth.

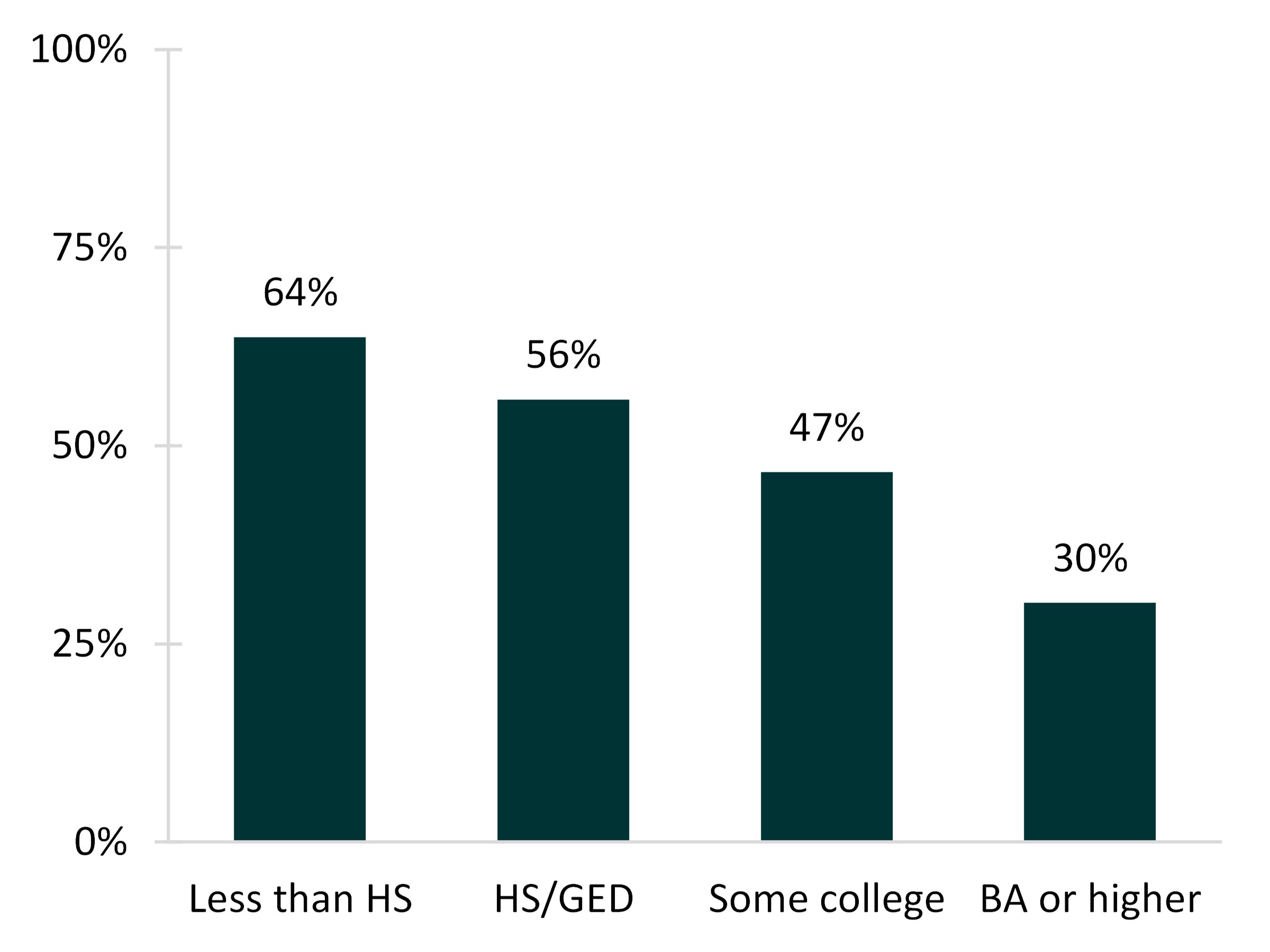

Education and Unintended Childbearing

- There is a clear educational gradient for experiences with unintended fertility among women at the end of their reproductive years in 2017.

- Nearly two-thirds (64%) of mothers 45-49 without a high school degree or GED had at least one unintended birth.

- Less than one-third (30%) of mothers with a college degree or higher had any unintended births.

Figure 3. Educational Differences in Experiencing Any Unintended Births Among Mothers Aged 45-49, 2017

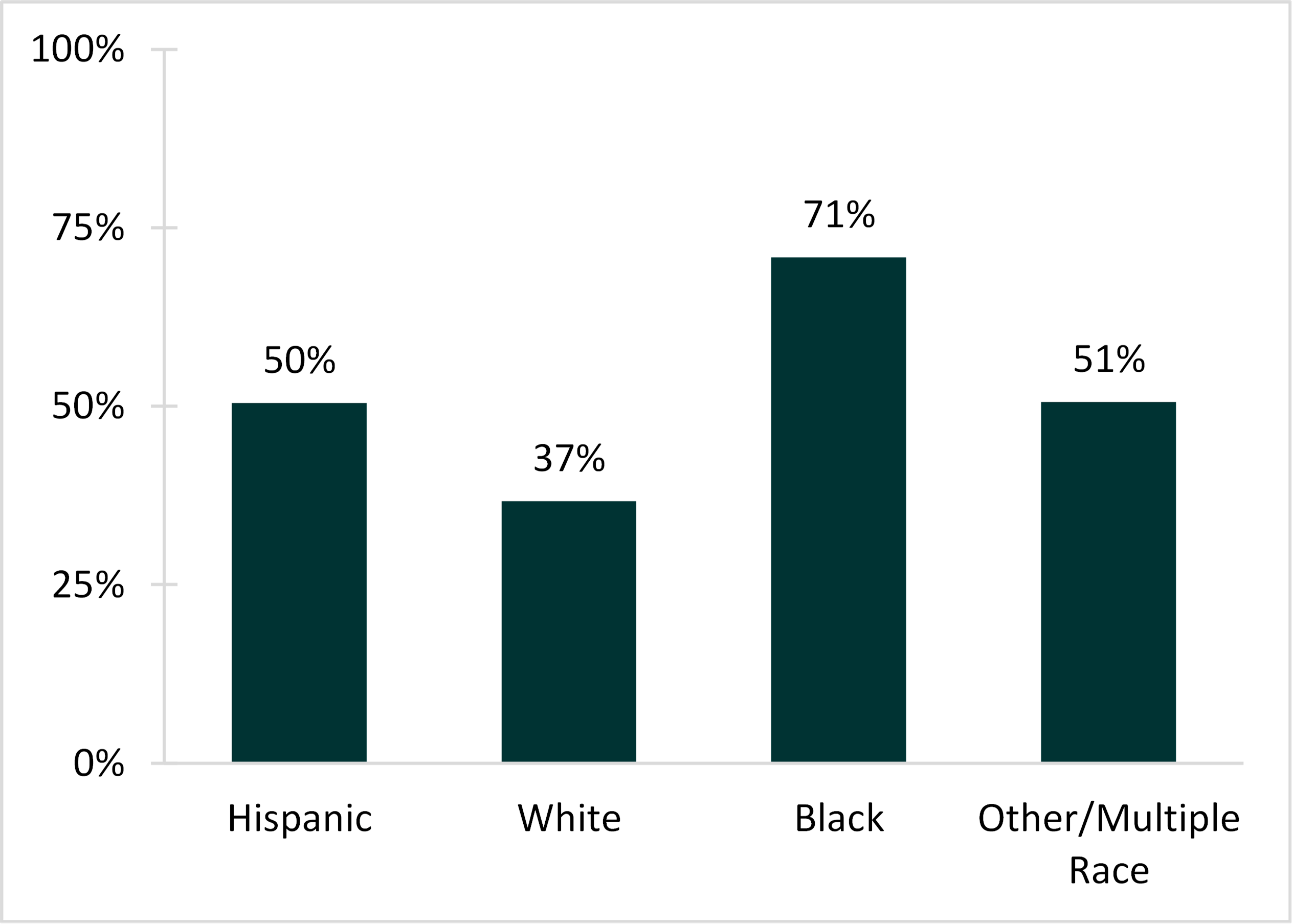

Race and Unintended Childbearing

- Unintended childbearing was least common among White mothers aged 45-49 in 2017. Less than two out of five (37%) White mothers had any unintended births.

- Unintended childbearing was most common among Black mothers – 71% of Black mothers had at least one unintended birth.

- Half of Hispanic, other-race, and multiracial mothers had at least one unintended birth.

Figure 4. Racial-Ethnic Differences in Experiencing Any Unintended Births Among Mothers Aged 45-49, 2017

Data Source

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2015-17 and 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth Public-Use Data and Documentation. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/index.html

References

- Guzzo, K. B. (2021). Thirty years of change in unintended births. Family Profiles, FP-21-01. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-21-01

- Guzzo, K. B. (2017). Women’s experiences of unintended childbearing. Family Profiles, FP-17-10. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-17-10

Suggested Citation

- Guzzo, K. B. (2021). Mothers’ experiences of unintended childbearing, 2017. Family Profiles, FP-21-03. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-21-03

Footnote

[1] The 2015-2019 cycle of the NSFG expanded its age range to 49 (up from age 45 in prior cycles) and released a slightly different set of variables on race-ethnicity. As such, the estimates in this profile are not directly comparable to profile FP-17-09.

This project is supported with assistance from Bowling Green State University. From 2007 to 2013, support was also provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the author(s) and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policy of any agency of the state or federal government.

Updated: 04/06/2021 01:50PM