Practical Science

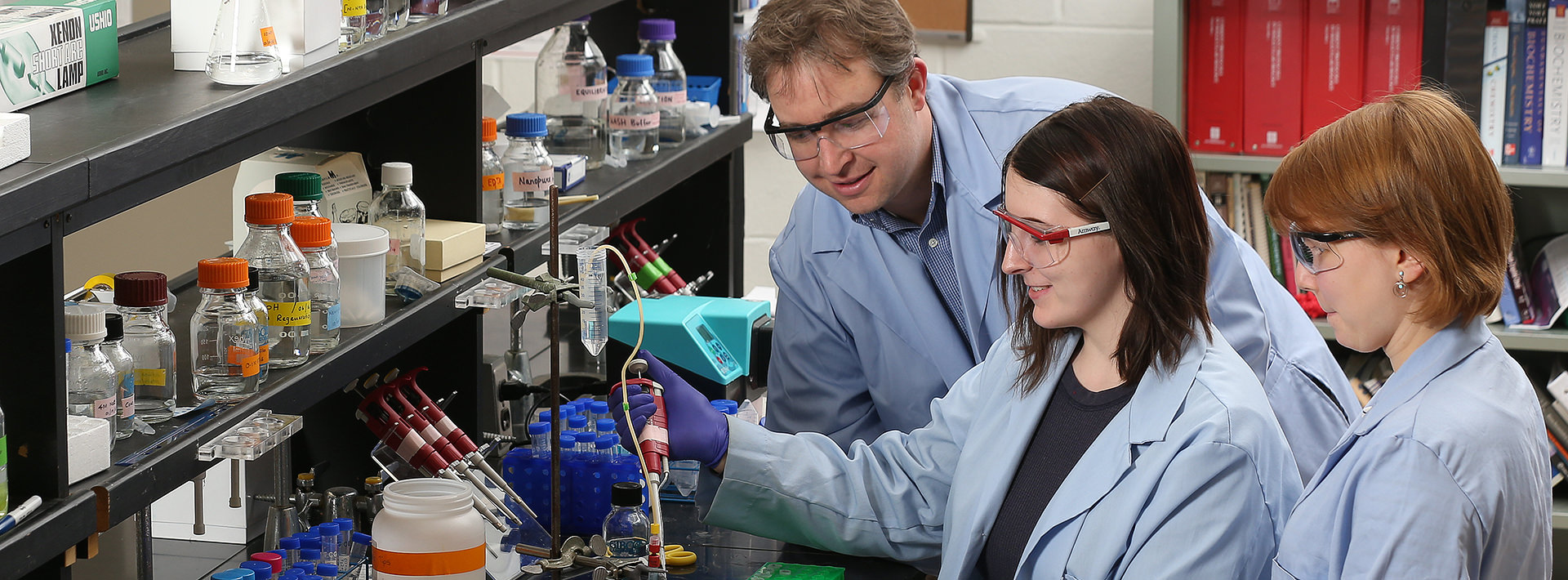

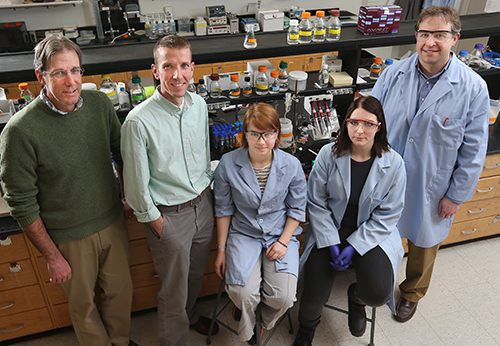

From left to right George Bullerjahn, Andrew Torelli, Mary Bauman, Clara Bittner and Dave Erickson At first glance it looks like your typical biochemistry lab. Groups of students are dressed in lab coats and safety glasses and are huddled around test tubes, notebooks and large pieces of scientific equipment. But, this wasn’t your average textbook lab. These undergraduates were working on genuine research where the outcomes were uncertain, and their results were forging new territory.

From left to right George Bullerjahn, Andrew Torelli, Mary Bauman, Clara Bittner and Dave Erickson At first glance it looks like your typical biochemistry lab. Groups of students are dressed in lab coats and safety glasses and are huddled around test tubes, notebooks and large pieces of scientific equipment. But, this wasn’t your average textbook lab. These undergraduates were working on genuine research where the outcomes were uncertain, and their results were forging new territory.

The lab experience was spearheaded by chemistry faculty Andrew Torelli, David Erickson and senior graduate student Mary Bauman. According to Torelli, the three of them worked together during the summer of 2014 to put together a fall semester laboratory course that was built around an actual research project, allowing students to focus on the scientific process, participate in experimental design and also communicate results.

“Our thoughts were that embedding a research component into the course would benefit students by giving them ‘real-world’ opportunities to apply the different concepts and techniques they were learning,” Torelli said. “We were hoping to avoid the ‘when will I ever need to know this?” question, and in doing so, increase student engagement and learning in the course.”

“It’s a lot better than just going out of the book, which says this is supposed to happen”Torelli, Erickson and Bauman worked with George Bullerjahn from the biological sciences department to choose the targets for study—proteins from a single-celled organism that’s recently been recognized as a major player in the nitrogen cycle. Bullerjahn also talked with the students at the beginning of the semester to underscore the broad importance of this research topic and kept tabs with the students’ progress throughout the semester. During the first half of the fall semester, students worked on learning lab techniques that were applied during the second half of the semester to characterize three previously unstudied proteins from the target organism.

“I’m really proud the students have succeeded in purifying their own proteins and collected data from experiments they helped design,” Torelli explained. “It’s an ambitious goal, but we hope we can publish some of the student results as we continue with this research project.”

Erickson served as the lab instructor and said students really had to reach outside their comfort zone and get used to not knowing what was going to happen in their experiments.

“With this kind of approach, the results of one week dictated the direction of the next week,” Erickson said. “You’ve got an experiment that you think you have down, and then you talk to someone else and you go in a different direction. There has been a bit of a dynamic nature—what proteins do we focus on and what directions do we go in— but they (the students) developed a set of techniques to handle anything that came their way.

“Characterizing an unknown protein in just a semester is pretty incredible. It’s very ambitious and I will love to see where it goes from here.”

The students worked in groups, but collaboration was encouraged to discuss problems.

“I think that worked out extremely well,” Erickson said. “If they didn’t come to us, they went to each other. In science you want to show that collaboration is often a good thing.”

In the middle of it all was Bauman, who never stopped moving around the lab. She easily maneuvered between answering a question to manipulating a large piece of equipment without skipping a beat. Bauman not only worked closely with the students in the lab, she also created handouts and recitation materials. Torelli said her energy and dedication were key to making this lab successful.

“It’s been fun and it’s nice to work with a small group doing research because they ask so many questions and reach for knowledge,” Bauman said. “The more they do, the more they appreciate what they’re doing.

“I don’t like cookbook labs—you don’t learn anything. Here they see how to use a particular skill or a technique and they can practically envision how things are done in real life. They’ve become more self-motivated and more organized and they appreciate what they’ve learned. These are good skills for when they graduate from college. Now they have real, hands-on lab experience.”

Torelli said the amount of time and effort the students put into the lab period was incredible, particularly since it was only worth one credit hour. But, the students said they understood their efforts had value.

“It’s a lot better than just going out of the book, which says this is supposed to happen,” said Clara Bittner, a junior majoring in chemistry from North Baltimore, Ohio. “Now it might happen or it might not and either one is okay. You write about it and you learn about it. You can’t predict the behavior of proteins.”

“You do have to interpret data on your own and things don’t go smoothly, which is what science is all about,” said Chris Sosnofsky, a senior majoring in biochemistry from Kawklin, Mich. “That’s what I like about it and what makes it different.”

“It’s way different from any lab I’ve been in,” said Max Beattie, a senior majoring in chemistry from Bowling Green, Ohio. “Before you could just ask a question, but now there’s no answer for those questions, you have to figure out why did something happen.”

This semester, two students are continuing the lab work and helping move it forward. Torelli is hoping work can continue in the fall with students looking at new proteins in the same organism—building on what was done last semester. Erickson also has ideas for the future.

“We may try different proteins and different experiments, but I think we can expand this to a wide variety of applications. One of the things the three of us have talked about is if there are other collaborations that could benefit from work done in this lab. I’d like to expand this more to other areas. It seems to be a lot more fun for them, and for us,” he said.

Updated: 12/02/2017 12:41AM