Faulkner Book Urges A More Physical Feminism

Sandra FaulknerBy Bonnie Blankinship

Sandra FaulknerBy Bonnie Blankinship

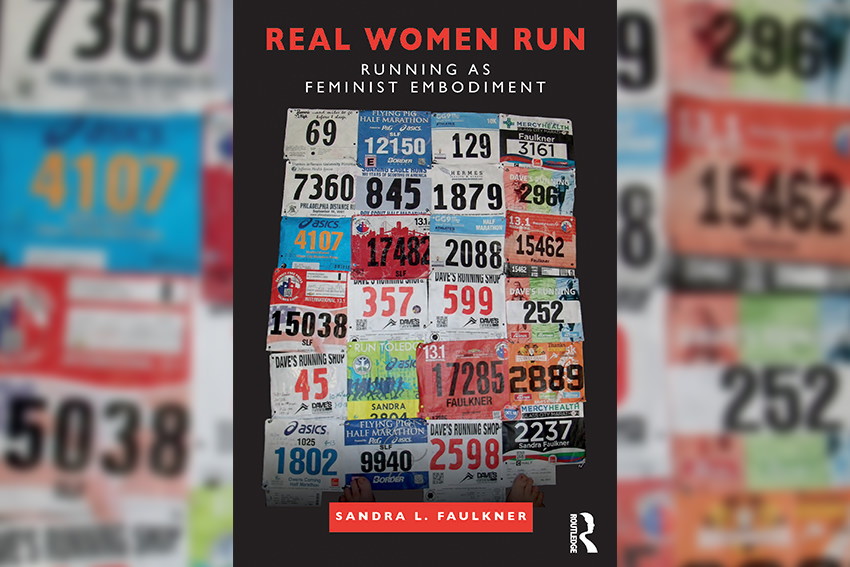

In a way, Dr. Sandra Faulkner has been preparing for her new book, “Real Women Run: Running as Feminist Embodiment,” her whole life. Since childhood she has been either running or wanting to run, and that desire to experience the physicality of her self has fed her personal and scholarly explorations of embodiment, identity and feminist theory.

Knitting all these threads into a coherent whole required an innovative approach. Published by Routledge, “Real Women Run” calls upon Faulkner’s personal experiences as a runner and a poet along with her expertise in poetic inquiry, ethnography and feminist analysis.

“I wanted to use my personal ethnography and connect it to larger societal influences, taking the personal to the public,” said Faulkner, a professor in the Department of Communication and director and graduate coordinator of the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies program. She includes journal entries from throughout her life, linked essays, haikus and poems, and stories of women who run, encompassing feminist, queer and running identities in a call for a more physical feminism.

“Embodiment is a big concept in feminist theory, but how do you get at that?” she wondered. “I saw poetry as a way in.”

The quiet, focused time she spends running allowed for concentration to reflect on and connect disparate threads, the rhythm of her steps and breath helping to clarify and distill her thoughts into haiku lines as she sought to reconcile the traditional mind-body split.

Faulkner also interspersed her field notes with narrative and haiku poetry in reaction to what she was hearing from her subjects to help interpret and analyze their experiences, along with the poems she wrote while running.

Learning to listen to and give equal value to corporeal experience can be a difficult step for the generations of women for whom feminism entailed almost a denial of the body and resistance to being defined by one’s biology, along with an insistence upon privileging the qualities of the mind. In terms of running, or other athletic activity, there are also the dominant cultural messages about women taking up space and what an athlete, in this case, a runner, looks like — and that is not what we usually think of as the typical woman.

Her content analysis of women’s running magazines, blogs and websites showed that even they fall prey to societal messages about body image and ideals of achievement. They are often beholden to advertisers eager to sell their clothing and other products, and, perhaps not surprisingly, the ads’ representations of women runners are not reflective of their immense diversity.

As Faulkner has found through her own running and her participant-observation research at road races and events such as the Gay Games, “You see all kinds of bodies. There’s been an explosion of women runners, of all ages.”

Her research drew upon her extensive field notes from interviewing these women about their experience, questioning them about why they run, what a good run feels like, how running fits into their lives, how they describe their running bodies, how they identify themselves. In addition to the exercise and health benefits of running, their reasons included running for charity, the social and community aspect, self-healing (as a group of women who survived violence in Iraq, as well as a group of homeless runners for whom running was empowerment and encouragement, attested), and the confidence and sense of accomplishment they gained.

Interestingly, the question of identity often evoked the least certain of women’s responses. They tended to downplay their involvement in running, characterizing it as just a hobby, hesitant to call themselves “runners.” Faulkner relates to this, especially as she has had long hiatuses from running because of multiple ailments and surgeries. Are you a runner when you are not actively running? Again, dominant cultural definitions shape women’s willingness to claim an identity that is properly theirs.

One thing that is certain is that running makes women feel stronger and more accepting of their bodies in appreciation of what they can do and where they can take them.

“It helps build discipline in other areas of your life,” Faulkner said. “When things are hard, you just keep going. Through my running, I know I can do other things as well. You can just compete against yourself. Society gives us a lot of messages about not being good enough, but this is one place I am good enough and I can bring that feeling into other areas of life.”

Updated: 02/07/2018 01:35PM