BGSU grad turns love of quirky baseball fields into digital art

Estimated Reading Time:

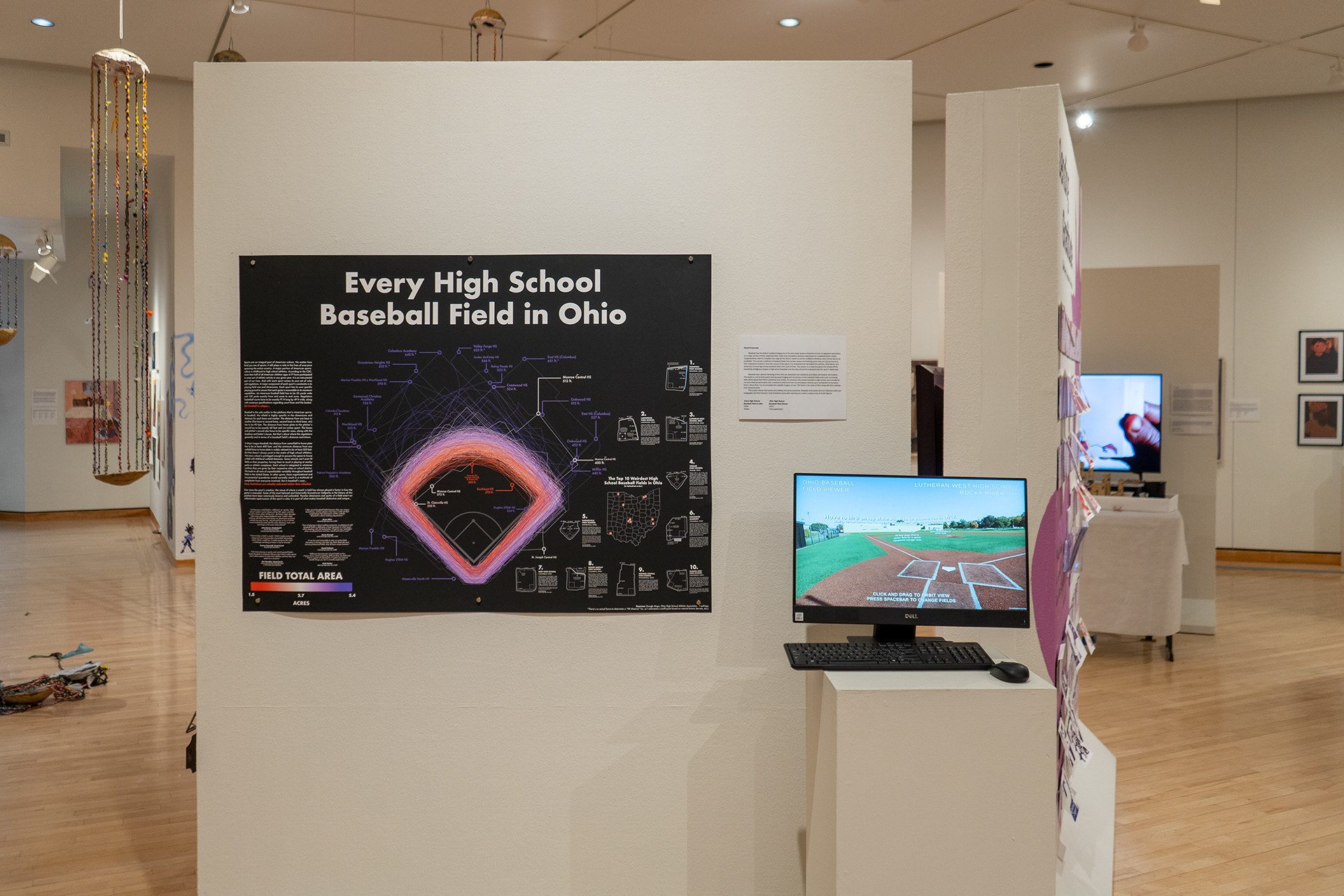

David Hrusovsky '23 uses his senior thesis project to map every high school baseball field in Ohio

By Nick Piotrowicz

As a high school baseball player, David Hrusovsky ’23 sometimes looked at his school’s home diamond with wonderment.

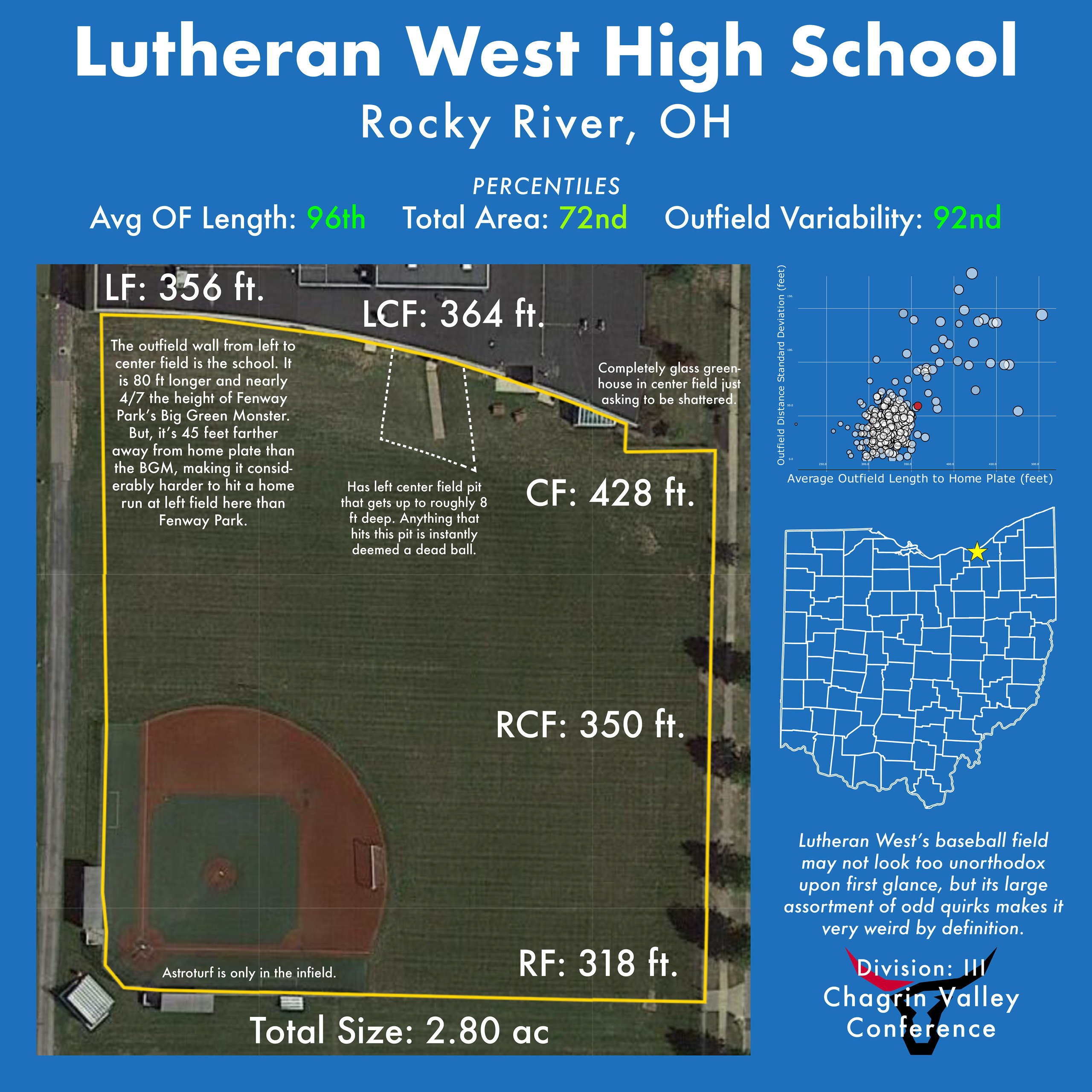

The ground rules at Lutheran High School West, located in the Cleveland suburb of Rocky River, are unusual, to say the least. Similar to Fenway Park in Boston, left field has a huge wall that requires a higher-than-normal launch angle to hit a home run.

Unlike Fenway, however, there is a pit — part of a driveway that goes into the school basement — that results in a dead ball if a batted ball reaches any part of it, and the big left-field wall is part of another structure: the actual school building.

To hit a home run to left field, a batter has to hit a ball hard enough to travel 356 feet from home plate, but also high enough that the ball flies onto the roof.

“The fence in left field was literally the wall of the school,” Hrusovsky said. “To hit a home run on the left side of the field, you had to hit it on top of the school. I was thinking, ‘There is no way any other school in the state has this.’”

So, during his freshman year at Bowling Green State University, Hrusovsky took on a pet project when the coronavirus pandemic hit by mapping each and every high school baseball field in Ohio.

The arduous process of creating a dataset required Hrusovsky to start from scratch by determining where each Ohio high school played baseball, then mapping its outfield distances, calculating total acreage and jotting down the little quirks that made each one unique.

Years later, when it came time for his senior thesis as a digital arts major at BGSU, he had the beginning of an idea: use the dataset to create something visual.

“I mostly wanted to see how my field stacked up against all the others in the state of Ohio in the beginning,” he explained. “Originally, it was a hobby, but when it came time for my senior thesis and we had to create an art piece that would go in the gallery, I thought, ‘Well, I have all of this data.’”

Refining the process

Hrusovsky initially started by documenting every high school baseball field in Ohio, but he has continued mapping baseball fields in even more U.S. states.

The process of creating and visualizing a dataset requires significant legwork in the data collection phase, beginning with finding every school in a state that fields a baseball team.

If Hrusovsky is lucky, a state’s high school athletics association website will feature addresses for each field, which allows him to begin mapping right away. For some states, he must determine whether a school has a home field at all.

“Originally, I was thinking, ‘Oh, man, how am I going to find all this?’” he said. “Each state at least attempts to have a high school association website. The OHSAA in Ohio has a list of all the schools that qualify for the various divisions of baseball, so I manually copied and pasted all of that into a spreadsheet, which is how I got the original list of names.”

In cases where there are no addresses on the state website, Hrusovsky tracks each field address down individually on school websites, and if the address isn’t there, either, he has to find them manually on Google Maps. Once he has the location, he can map its dimensions in about 10 minutes.

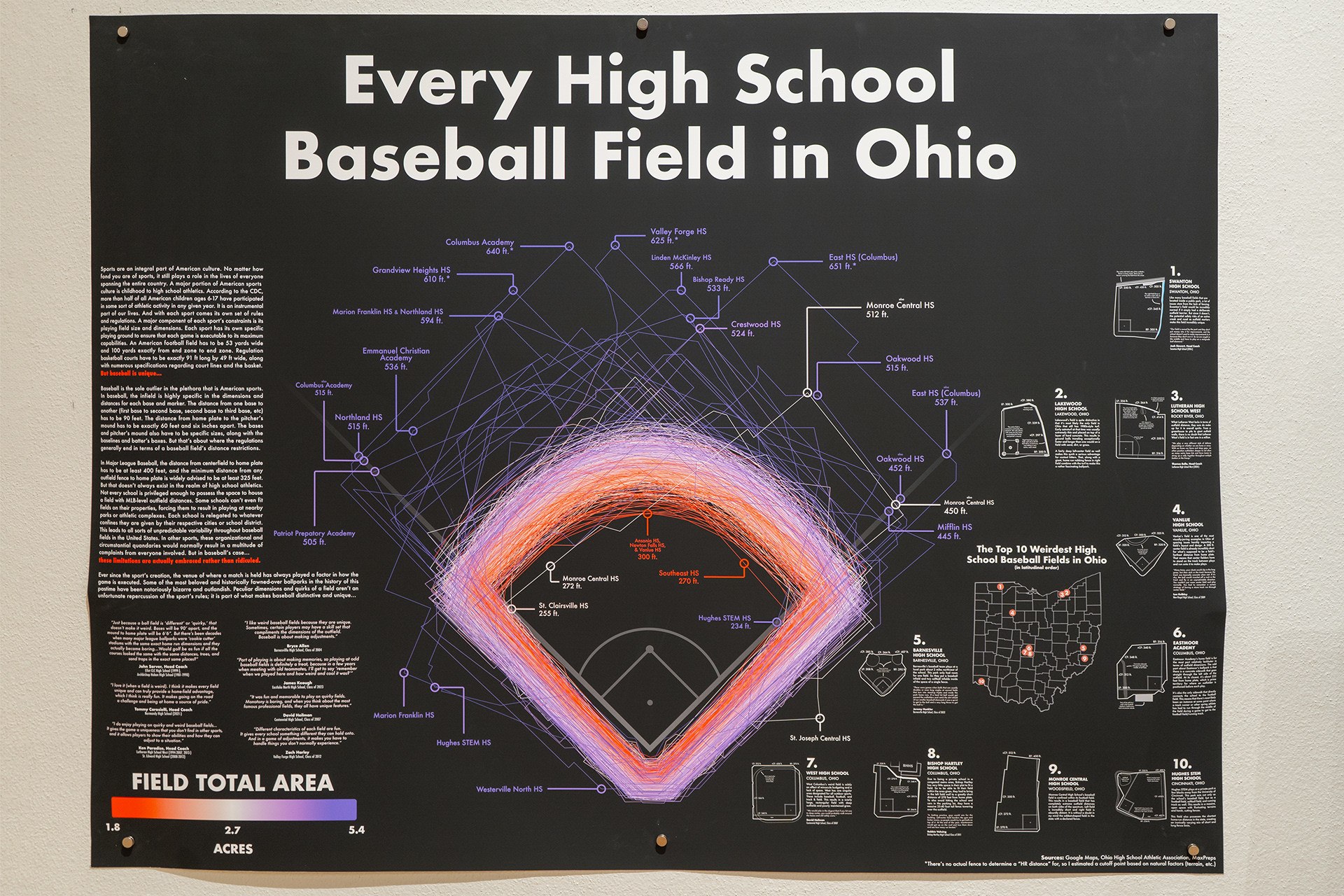

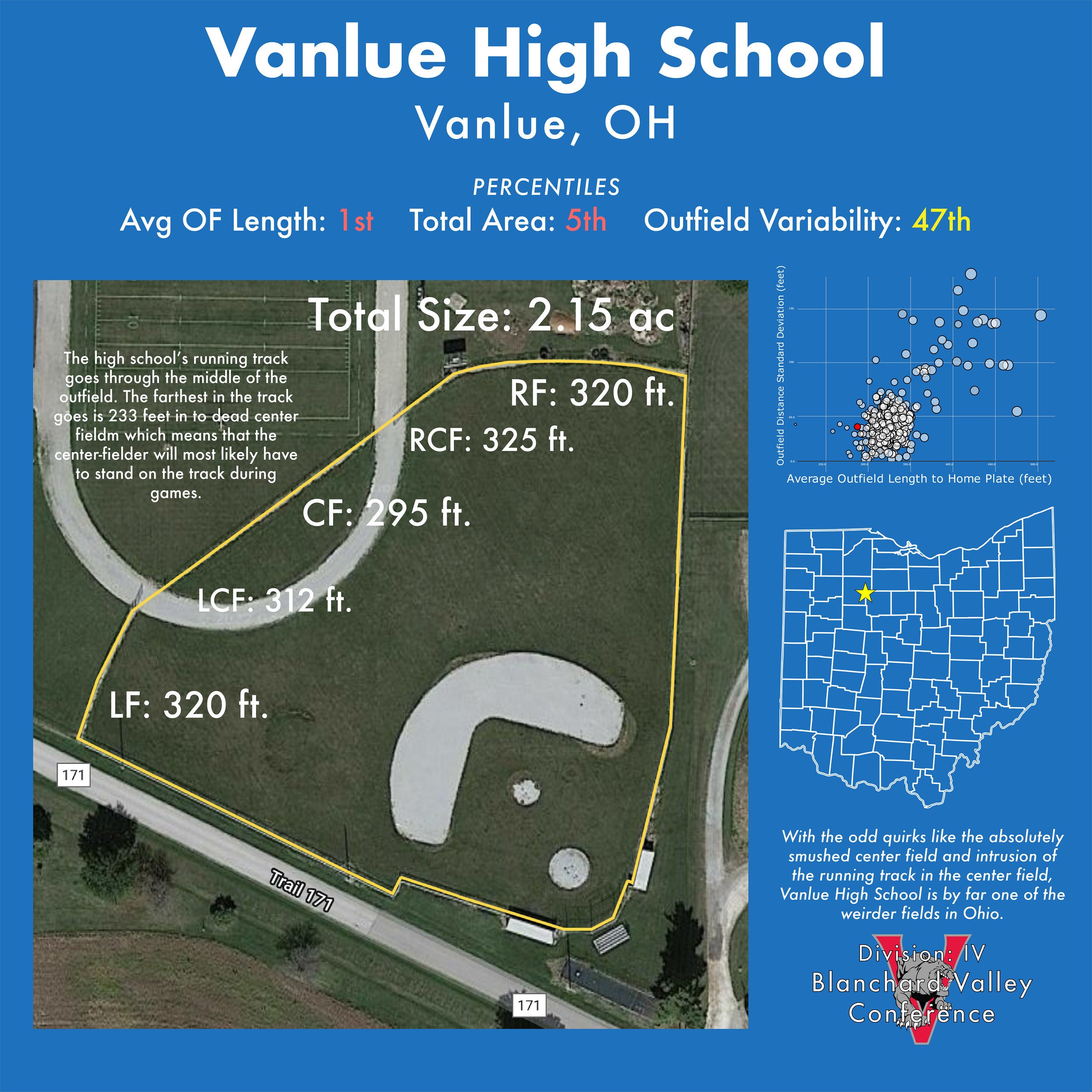

From the very beginning, Hrusovsky's research found more than a few unique playing fields in Ohio. Valley Forge High School is a Herculean 625 feet to center, while the center field fence at Vanlue High School is within reach for even the most light-hitting second baseman at 300 feet.

For his thesis, the trick for Hrusovsky was turning the cavernous spreadsheet into something visual. Digital arts students learn coding as part of their studies at BGSU, and associate professor Bart Woodstrup said Hrusovsky did exceptionally well at turning the rigidity of code into visual art.

Much like the baseball field that spurred the dataset, Hrusovsky’s project idea was a unique one.

“David’s project was this great marriage of his personal interest and personal narrative — he was a baseball player who loved looking at all these quirks about baseball fields — and combined them with the skills he was learning with code,” Woodstrup said. “The challenge was: is it art? He had to convince the faculty that what he was doing was art because he certainly was doing something very different from what all the other students were doing.”

Data Becomes Art

Unlike most other sporting surfaces, baseball’s playing fields are not uniform. For example, a ball hit 370 feet to left-center is comfortably into the left-field seats for a home run at Citi Field, the New York Mets’ home ballpark. Across town, though, a ball hit the same distance in the same place at Yankee Stadium — where the fence is 399 to left-center — is well within play.

In their own way, each diamond tells a story.

By gathering, documenting, comparing and visualizing these data, what Hrusovsky really was doing was telling a story one field and one state at a time.

In the spring of 2022, Hrusovsky began posting his findings on the platform formerly known as Twitter, where he found something interesting: There was an audience of people who were just as fascinated by these findings as he was.

Within each baseball field is a story, which BGSU graduate David Hrusovsky documented with his digital arts thesis. Lutheran High School West, left, was the inspiration for the project, which found other unique baseball fields like Vanlue High School. (David Hrusovsky)

Within that experience, Hrusovsky found a pathway into creating something that people found engaging, which Woodstrup said is the ultimate goal of any form of art.

“Art has to be culturally significant and resonate with an audience,” Woodstrup said. “Most people think of art as something you hang on the wall to make your room prettier, but I have a lot of things on my wall that make my room prettier that aren’t culturally significant. What David’s work does is address something a culture recognizes as entertaining and interesting.

“When people look at the work he’s done and become nostalgic about their own experience or inquisitive about baseball diamonds, they’re interacting with it in a significant way — and that’s what makes it art.”

As Hrusovsky expanded the project beyond Ohio, he began creating connections between a field's "weirdness" and the other external factors around it.

The overall findings have revealed that unique fields and the size of the local population appear correlated.

“It took a few states to get there, but I have found that states with higher populations tend to have more random fields,” he said. “The same thing goes for population density. I’m spotting a pretty high correlation between population density and odd fields with large variations in distances.

“In some places, they have no space at all, so they have to put a field wherever they can put it. Other places, they might have a lot of room, so their field is giant. It’s polar opposites of the spectrum.”

By meticulously documenting fields, Hrusovsky perhaps found a pathway into how to use his abilities in the future, Woodstrup said.

“I really think the senior project he did with us at BGSU was not the end of the project,” Woodstrup said. “It was just the beginning for David.”

Hrusovsky, a lifelong Cleveland baseball fan who gained some local fame wearing a SpongeBob SquarePants costume to match Guardians outfielder Oscar Gonzalez’s at-bat song, said the project has been a labor of love, but something that showed what is possible with the skill set he refined at BGSU.

“I really loved researching and finding creative ways of displaying that research,” he said. “This didn’t start out as a data visualization project, but it became that because of how much I liked to use my digital arts skills that I learned in classes at BGSU.

“It’s really a tribute to the classes I took, the experiences I had and the confidence I gained to go for it and post some of these online.”

Related Stories

Media Contact | Michael Bratton | mbratto@bgsu.edu | 419-372-6349

Updated: 11/17/2023 01:03PM